Dissecting RANDU

Introduction

Today finally the Train Your Brain book by Paweł Prałat and me is finally available. In the book we argue that using computer support can help solve mathematical problems.

In this post I thought of doing the reverse — consider a classical computing problem that can be better understood using mathematics. Here I concentrate on the computational part, but all the theory needed to rigorously study what I discuss is presented in the Train Your Brain book.

The topic I want to tackle today is why devising a good pseudo random number generator is hard. I will use the classical RANDU generator to highlight potential problems that one might encounter in practice.

This post was tested under Julia 1.5.3, DataFrames.jl 0.22.2, FreqTables.jl 0.4.2, HypothesisTests.jl 0.10.2, Pipe.jl 1.3.0, and PyPlot.jl 2.9.0.

As a warning note that some of the computations we do in this post can take up

to several minutes and require at least several GB of RAM (I used @time to

highlight the most expensive steps), so if you run my code you should take this

into account.

Let us get started!

Setting up the scene

The RANDU generator produces floating point values from the \((0,1)\) interval using the following rule. Let \(S_i\) be the state of the generator at time \(i\). Then is next state is defined as:

\[S_{i+1}=65539S_i \mod 2^{31},\]and the produced float value is \(S_{i+1} / 2^{31}\).

We start with loading the libraries we will use in this Julia session:

using DataFrames

using FreqTables

using HypothesisTests

using Pipe

using PyPlot

using Random

using Statistics

Now implement the RANDU generator:

const RANDU_CONST = 0x00010003

mutable struct Randu <: AbstractRNG

state::UInt32

end

Random.seed!(r::Randu, state::UInt32) = (r.state = state; return r)

Base.copy(r::Randu) = Randu(r.state)

function Random.rand(r::Randu,

::Random.SamplerTrivial{Random.CloseOpen01{Float64}})

s = r.state

s = (s * RANDU_CONST) & 0x7fffffff

r.state = s

return s / 0x80000000

end

Observe that we use UInt32 for all computations and as \(2^{31}\) is a divisor

of \(2^{32}\) we can safely ignore the overflow - we simply look at the lowest

31 bits of the generated numbers, which is done by performing the & 0x7fffffff

operation.

Now we are ready to get started with using this generator to produce Float64

pseudo random values from the \((0,1)\) range.

Not enough randomness

First we want to produce random permutations using the generator. Here is the code that counts how many distinct permutations we get if the length of the permutation is 64 and we produce 10,000,000 of them.

count_permutations(rng::AbstractRNG) =

mapreduce(push!, 1:10_000_000, init=Set{Vector{Int}}()) do _

sortperm(rand(rng, 64))

end |> length

Let us start with using MersenneTwister that is currently used as a default

generator in Julia:

julia> @time count_permutations(MersenneTwister(11))

64.585667 seconds (30.11 M allocations: 12.058 GiB, 34.31% gc time)

10000000

We can see that we got no duplicates. Now let us test our RANDU generator:

julia> @time count_permutations(Randu(11))

61.817341 seconds (30.00 M allocations: 12.052 GiB, 31.82% gc time)

8388608

julia> @time count_permutations(Randu(12))

39.189380 seconds (30.00 M allocations: 11.841 GiB, 19.51% gc time)

2097152

Now we got many duplicates, and we see that 12 produced many more than 11.

Let us start with trying to understand what we should expect in this case. We have \(64!\) permutations (buckets) and \(10^7\) values so the probability of not seeing any duplicate is:

\[1 - \prod_{i=0}^{10^7-1}\left(1-\frac{i}{64!}\right)\]This value can be approximated from above by (where the above formula comes from and how to do such approximations is explained in our book):

\[1 - \exp\left(-\frac{10^7\cdot (10^7-1)}{2\cdot 64!-10^7}\right)\]This can be easily computed using Julia:

julia> Float64(1 - exp(-10_000_000*(10_000_000-1)/

(2*(factorial(big(64))-10_000_000))))

3.9726375353434445e-76

As you can see the probability of seeing any duplicate is extremely low, so there must be some flaw in the RANDU generator.

In this case the problem is that it does not produce enough randomness. We can see that the generator has at most \(2^{31}\) states (actually it has less as we will find out soon) and it seems not enough for our purposes.

Let us investigate it in more detail. Let us first check for what smallest positive \(c\) we have:

\[65539^c \equiv 1 \mod (2^{31})\]as then we will have that

\[S_1 \equiv S_{c+1} \mod (2^{31})\]and thus get a cycle. Here is the code:

julia> function find_min_power()

m = RANDU_CONST

i = one(UInt32)

while m & 0x7fffffff != 1

m *= RANDU_CONST

i += one(UInt32)

end

return i

end

find_min_power (generic function with 1 method)

julia> find_min_power()

0x20000000

julia> RANDU_CONST^0x20000000 & 0x7fffffff

0x00000001

and we see that \(c=2^{29}\) (again why it is \(2^{29}\) and how it could have been computed using pen and paper is explained in our book). This means that given any starting seed \(S_1\) we cannot generate more than \(2^{29}\) distinct values. This is not much indeed for current computing standards. However, let us investigate why seed 12 was much worse than seed 11. Here is the code:

julia> function get_cycles()

cycle = zeros(UInt8, 0x80000000)

c = 0x1

for k in 1:2^31-1

i = k

cycle[i] != 0x0 && continue

while cycle[i] == 0x0

cycle[i] = c

i = (i * RANDU_CONST) & 0x7fffffff

end

@assert i == k # we should get a cycle

c += 0x1

@assert c != 0x0 # make sure we do not have more than 255 cycles

end

return cycle

end

get_cycles (generic function with 1 method)

julia> @time cycle = get_cycles()

127.491600 seconds (2 allocations: 2.000 GiB, 0.29% gc time)

2147483648-element Array{UInt8,1}:

0x01

0x02

0x01

0x03

0x04

0x02

0x04

0x05

0x01

0x06

⋮

0x0a

0x01

0x06

0x01

0x08

0x04

0x06

0x04

0x00

julia> freq_cycle = sort(freqtable(cycle), rev=true)

61-element Named Array{Int64,1}

Dim1 │

──────┼──────────

0x01 │ 536870912

0x04 │ 536870912

0x02 │ 268435456

0x06 │ 268435456

0x03 │ 134217728

0x08 │ 134217728

0x05 │ 67108864

0x0a │ 67108864

0x07 │ 33554432

⋮ ⋮

0x33 │ 8

0x38 │ 8

0x35 │ 4

0x3a │ 4

0x37 │ 2

0x39 │ 2

0x3c │ 2

0x00 │ 1

0x3b │ 1

julia> freqtable(freq_cycle)

30-element Named Array{Int64,1}

Dim1 │

──────────┼──

1 │ 2

2 │ 3

4 │ 2

8 │ 2

16 │ 2

32 │ 2

64 │ 2

128 │ 2

256 │ 2

⋮ ⋮

2097152 │ 2

4194304 │ 2

8388608 │ 2

16777216 │ 2

33554432 │ 2

67108864 │ 2

134217728 │ 2

268435456 │ 2

536870912 │ 2

And we see that we have two cycles having \(2^{29}\) length and many shorter cycles. The shortest one has length 1, let us check if this is indeed the case:

julia> x = UInt32(only(findall(==(0x3b), cycle)))

0x40000000

julia> x * RANDU_CONST & 0x7fffffff

0x40000000

So if we are unlucky with the choice of the initial seed we will get the cycle

of length 1. This phenomenon is called a bad seed problem in pseudo random

number generators. However, a cursory look at cycle variable suggests that

it is the case that all odd numbers are good seeds (producing cycle of length

\(2^{29}\)). Let us check this:

julia> foreach(enumerate(cycle)) do (i, v)

@assert iseven(i) ⊻ (v == 0x1 || v == 0x4)

end

julia>

We got no error so indeed this the case. Actually the two longest cycles contain two groups of odd numbers that respectively are congruent to 1 and 3, or 5 and 7 modulo 8 as we can see here:

julia> ([1, 3, 5, 7] .* RANDU_CONST) .% 8

4-element Array{Int64,1}:

3

1

7

5

This, in particular, shows us that low bits of the generated numbers show a pattern so RANDU is not well suited for generation of integers. But maybe it is good when generating floats?

Before checking this let me just summarize that we have up to this point learned that if we use a good (i.e. odd) seed we have a generator that has a cycle of \(2^{29}\). This means that it is essentially only useful if we generate very few random numbers by todays standards. Above we saw that this causes a problem when generating permutations. Before we move on let us check out another scenario of generating binary numbers:

julia> function gen2(rng::AbstractRNG)

means = Float64[]

for _ in 1:1000

s = 0

for _ in 1:10^8

s += rand(rng) < 0.5

end

push!(means, s / 10^8)

end

return var(means), quantile([var(rand(means, 1000)) for _ in 1:10000],

[0.025, 0.975])

end

gen2 (generic function with 1 method)

julia> @time gen2(Randu(11))

124.834623 seconds (10.02 k allocations: 77.684 MiB)

(3.806128771508955e-9, [3.540403887824998e-9, 4.062688436887708e-9])

julia> 0.25 / 10^8 # we should get approximately this value

2.5e-9

and we can see that the variance produced for \(10^8\) trials is much to large (note that doing 1000 repetitions of the experiment ensured that the differences are significant, which we checked using bootstrapping). Conversely, we could have easily made the variance too small if we use e.g. \(2^{29}\) trials (as you can see below we got exactly the same value 100 times — for sure not producing enough variance):

julia> function gen2_v2(rng::AbstractRNG)

means = Float64[]

for _ in 1:100

s = 0

for _ in 1:2^29

s += rand(rng) < 0.5

end

push!(means, s / 2^29)

end

return freqtable(means)

end

gen2_v2 (generic function with 1 method)

julia> @time gen2_v2(Randu(11))

62.797411 seconds (42 allocations: 5.156 KiB)

1-element Named Array{Int64,1}

Dim1 │

──────┼────

0.5 │ 100

Linearity in higher dimensions

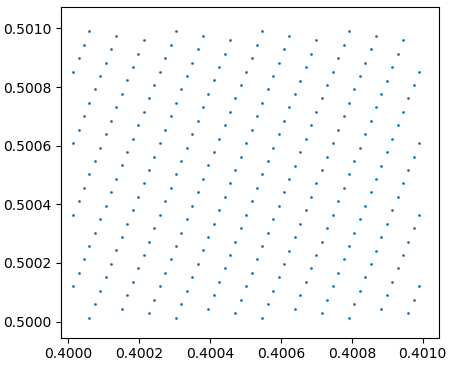

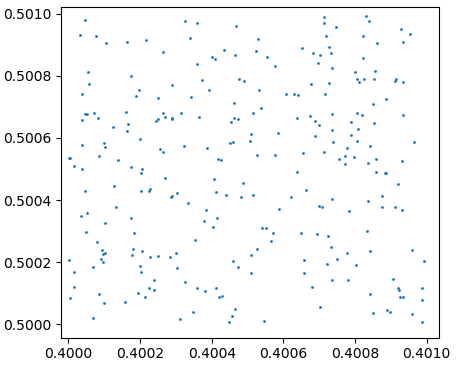

Have a look two plots that were generated using this code:

function plot_square(rng::AbstractRNG)

v = Tuple{Float64, Float64}[]

for i in 1:2^28

x, y = rand(rng), rand(rng)

if 0.4 < x < 0.401 && 0.5 < y < 0.501

push!(v, (x,y))

end

end

scatter(getindex.(v, 1), getindex.(v, 2), s=1)

end

Here are the plots:

plot_square(Randu(11))

plot_square(MersenneTwister(11))

The RANDU plot looks oddly regular. The points seem to lie on parallel lines.

It is clear that \(S_{i+1} / 2^{31} - 65539\cdot S_{i} / 2^{31}\) is an integer as \(S_{i+1}=65539S_i \mod 2^{31}\). However, if we had only this relationship would not get the pattern we see above. Let us look for other lines of this type (we limit ourselves to small values of pairs defining the lines):

julia> function find_2d()

for a in 1:RANDU_CONST

b = a * RANDU_CONST & 0x7fffffff

a + b <= RANDU_CONST + 1 && @show a, -b

b = 0x80000000 - b

a + b <= RANDU_CONST + 1 && @show a, b

end

end

find_2d (generic function with 1 method)

julia> find_2d()

(a, -b) = (1, -65539)

(a, b) = (32766, 32774)

(a, -b) = (32767, -32765)

Now, of the two pairs (32766, 32774) and (32767, -32765) which one can be

expected to produce bigger spacing between the lines? Note that both produce

values in the similar width of the range. However, (32766, 32774) produces

only odd values (as we assume to use odd seed value), while (32767, -32765)

produces both even and odd values because:

where \(p\) is an integer, and after rearranging we get:

\[\frac{(65539a+b) S_i + 2^{31}ap}{2^{31}}\]Now for both our \((a, b)\) pairs we have that \(65539a+b=2^{31}\) so it reduces to:

\[S_i+ap.\]Since \(S_i\) is odd, we see that for \(a=32766\) this is always an odd number, while for \(a=32767\) it can be either even or odd number as discussed.

So for (32766, 32774) we expect to get \((32766+32774)/2= 32770\) distinct

integer values. Let us check this:

julia> let ru = Randu(11), s = Set{Int}()

for _ in 1:2^28

v = Int(32774*rand(ru)+32766*rand(ru))

@assert isodd(v)

push!(s, v)

end

length(s)

end

32770

Having 32700 parallel lines on which the points lie is bad (we can see this above), but probably not prohibitive. The real problem starts when we look at the triplets of points and check if we can put them on a few planes (again we limit ourselves to only small values of pairs defining the lines):

julia> function find_3d()

a = 1

for b in 0:RANDU_CONST, signb in [-1, 1]

c = (a * RANDU_CONST^2 + signb * b * RANDU_CONST) & 0x7fffffff

a + b + c <= RANDU_CONST && @show a, signb*b, -c

c = 0x80000000 - c

a + b + c <= RANDU_CONST && @show a, signb*b, c

end

end

find_3d (generic function with 1 method)

julia> find_3d()

(a, signb * b, -c) = (1, -5, -65530)

(a, signb * b, c) = (1, -6, 9)

(a, signb * b, -c) = (1, 32761, -32756)

(a, signb * b, -c) = (1, -32772, -32765)

Bam – we got a very bad (1, -6, 9) tuple! Now we understand the reason for

the famous RANDU plot that you can see in Wikipedia artice I linked

above:

Before we move on let us check the same with our code:

julia> let ru = Randu(11), s = Set{Int}()

for _ in 1:ceil(Int, 2^29 / 3)

push!(s, 9*rand(ru) - 6*rand(ru) + rand(ru))

end

length(s)

end

15

But why it is a problem? Let us illustrate it by splitting each of three dimensions into \(16\) bins (so we get \(16^3\) bins in total). Finally we use the DataFrames.jl package (which I assume everyone was waiting for :), as it was announced in the introduction and every story teller tries to follow Чеховское ружьё principle):

julia> @time res3d = let

df = DataFrame(x1=UInt8[], x2=UInt8[], x3=UInt8[])

ru = Randu(11)

for _ in 1:ceil(Int, 2^29 / 3)

push!(df, trunc.(UInt8, 16 .* (rand(ru), rand(ru), rand(ru))))

end

df

end

52.469085 seconds (1.25 G allocations: 18.675 GiB, 3.29% gc time)

178956971×3 DataFrame

Row │ x1 x2 x3

│ UInt8 UInt8 UInt8

───────────┼─────────────────────

1 │ 0 0 0

2 │ 0 2 7

3 │ 11 13 13

4 │ 1 0 9

5 │ 3 14 3

6 │ 8 2 14

7 │ 2 15 5

⋮ │ ⋮ ⋮ ⋮

178956965 │ 4 5 3

178956966 │ 4 12 0

178956967 │ 15 8 11

178956968 │ 6 11 11

178956969 │ 15 10 15

178956970 │ 15 3 6

178956971 │ 7 0 0

178956957 rows omitted

julia> @time agg3d = @pipe res3d |>

groupby(_, [:x1, :x2, :x3]) |>

combine(_, nrow) |>

sort(_, :nrow, rev=true)

5.939132 seconds (216 allocations: 4.667 GiB, 0.78% gc time)

3840×4 DataFrame

Row │ x1 x2 x3 nrow

│ UInt8 UInt8 UInt8 Int64

──────┼────────────────────────────

1 │ 5 1 7 78360

2 │ 6 7 3 78300

3 │ 3 12 12 78268

4 │ 7 13 12 78215

5 │ 2 5 11 78201

6 │ 0 2 9 78201

7 │ 5 2 13 78199

⋮ │ ⋮ ⋮ ⋮ ⋮

3834 │ 10 2 9 6339

3835 │ 12 15 3 6336

3836 │ 10 0 13 6332

3837 │ 11 3 4 6331

3838 │ 7 3 8 6329

3839 │ 6 3 3 6313

3840 │ 3 0 12 6299

3826 rows omitted

julia> nrow(agg3d), 16^3

(3840, 4096)

julia> nrow(res3d) / 16^3

43690.666748046875

What do we see here. We used a bit over \(2^{29}\) random numbers (so we went through the whole cycle of the generator). We got 3840 non-empty bins out of a total of 4096 possible bins. Also we can see that as the average bin size is around 43691 we have bins that are almost twice as populated and bins that contain very small number of values. An extremely unlikely situation as we can see with this test:

julia> bins = zeros(Int, 16^3);

julia> copyto!(bins, agg3d.nrow);

julia> pvalue(ChisqTest(bins))

0.0

The reason is obvious – we have points lying on fifteen planes and using \(16\times16\times16\) grid we are very often hitting the holes between the planes (which also means that to balance this sometimes we are hitting overly dense regions of points by other bins). This clearly shows that using RANDU to perform e.g. integration using MonteCarlo simulation in higher dimensions is not advisable.

Let us give a simple example of this. We want to integrate a function:

\[f(\mathbf(x)) = 20^n \exp\left(-20\sum_{i=1}^nx_i\right),\]where \(n\) is a number of dimensions and will range from \(1\) to \(4\). We want to calculate its integral over \([0,1]^n\). Analytically we know it is equal to \((1-\exp(-20))^n\), so it is almost \(1\).

Let us check the results:

julia> let ru = Randu(111)

for n in 1:4

int = mean(f(rand(ru, n)) for _ in 1:10^8)

@show n, int

end

end

(n, int) = (1, 0.9999974000942274)

(n, int) = (2, 1.0002307988280261)

(n, int) = (3, 1.3654740670592842)

(n, int) = (4, 2.355245785641749)

Note how bad it becomes in dimension higher than 2 (I omit testing statistical significance of the deviation for \(10^8\) samples and encourage you to perform it as an exercise).

We can compare it to MersenneTwister results:

julia> let mt = MersenneTwister(111)

for n in 1:4

int = mean(f(rand(mt, n)) for _ in 1:10^8)

@show n, int

end

end

(n, int) = (1, 0.9994916961823186)

(n, int) = (2, 1.000145832437786)

(n, int) = (3, 0.9932430835430406)

(n, int) = (4, 0.9993585894631343)

which produces following what would normally be expected.

Concluding remarks

I hope this post highlighted typical problems the pseudo random number generators may posses, and the practical consequences of these issues. I also tried to show how nicely such an analysis can be performed using the Julia language and the packages from the JuliaData ecosystem.

I encourage you to play around with different pseudo random number generators and check if they pass or fail the tests I have presented. If you want to learn more about testing pseudo random number generators then this article is a good place to start.

Happy New Year!